The 3 point shot is quickly becoming one of the most important plays to perfect on the offensive end. Coaches are beginning to realise the untapped potential of the long-range shot, and are starting to focus more of their offensive plays on getting good shooters open for 3 point shots, especially in the corner, which is becoming the most efficient play in basketball. Players are spending more time practicing the 3 point shot, and we’re seeing a lot more 4s and 5s working on the craft and floating around the perimeter, an almost unheard-of concept only a decade ago.

The league average for 3 point shots in the 2015-16 season was 35.4%, for an expected points per attempt of 1.062, vs the 2 point shot which is made at a league average of 49.1%, for expected points per shot of 0.982. The concept of Nash Equilibrium would suggest that there is an inefficiency in the shot selection of offenses, so we can only expect 3 point attempts to increase in the future. For those who don’t know, Nash Equilibrium is the idea that strategy selections in a game will eventually even out as better strategies are chosen more by players, and countered more often by their opponents. Applied to basketball, it suggests that offenses will continue to shoot more 3s, and defenses will focus more attention to 3s, until the expected points for 3s v 2s is the same, a state of equilibrium. For this reason, a good understanding of where these extra shots should come from, and who the best 3 point shooters are is an important factor to any decision maker on the basketball court.

Currently, there exist a handful of incomplete metrics for measuring the effectiveness of a 3 point shooter. 3 point percentage is nice, it gives you a good idea of the likelihood of one of their shots getting in the hoop, but as with any rate statistic, it comes with flaws. Most of them stem from the fact that shot selection and volume account for so much of the minute differences between good and great shooters. The best 3 point shooter of all time according to 3P% is Steve Kerr, who had a career rate of 45.4%. That’s great, but he only made an average of 0.8 3s per game. Contrast this with Steve Nash, who shot at a lower 42.8% but made 1.4 3s per game. Shooting at a great click is useful, but only if you use it. Having a high 3 point percentage is good, but it’s useless if you don’t use it as much as a player with a slightly lower percentage. So 3 point percentage can’t be our only metric for deciding 3 point effectiveness.

So if pure efficiency isn’t going to cut it, let’s try a volume stat instead. 3 Pointers per game should be a good measure. If 3 points are worth more than 2, the more made 3s the better, right? Wrong. If you go by 3P/G, LeBron James (1.4) is just as good of a 3 Point shooter as Steve Nash (1.4). But LeBron James’ career mark is a meagre 34.0%, as opposed to Steve Nash at a much better rate of 42.8%. Nash (3.2 3PA/G) takes 0.8 less attempts than LeBron (4.0 3PA/G) to make his 3s, so Nash is clearly a better shooter, and going purely off volume metrics isn’t going to be very helpful either. What is needed is a metric that effectively combines efficiency with a volume of efficiency.

The ultimate mark of a good 3 point shooter should be the amount of points that they score greater than the expected points off every possession which they end with a 3 point shot. Simplified, this is “points off threes subtract expected points”. The method for determining expected points off a possession was to take the average Offensive Rating for the league (Points/100 possessions) and divide by 100. This gives an expected points per possession for the 2015-16 season of 1.064. The formula for calculating how much better than 1.064 points per possession each 3 point shooter was, is 3*3P – 1.064*3PA. Now we have our formula, we can apply it to every player in the league to judge their 3 point effectiveness. All we need is a name — I started using 3PTEPA for 3PT Expected Points Added as a tip to some of Baseball’s divisive sabremetrics, and eventually settled on 3PTx, 3PT Expected. Plus, 3PTx sounds pretty edgy so I went with it.

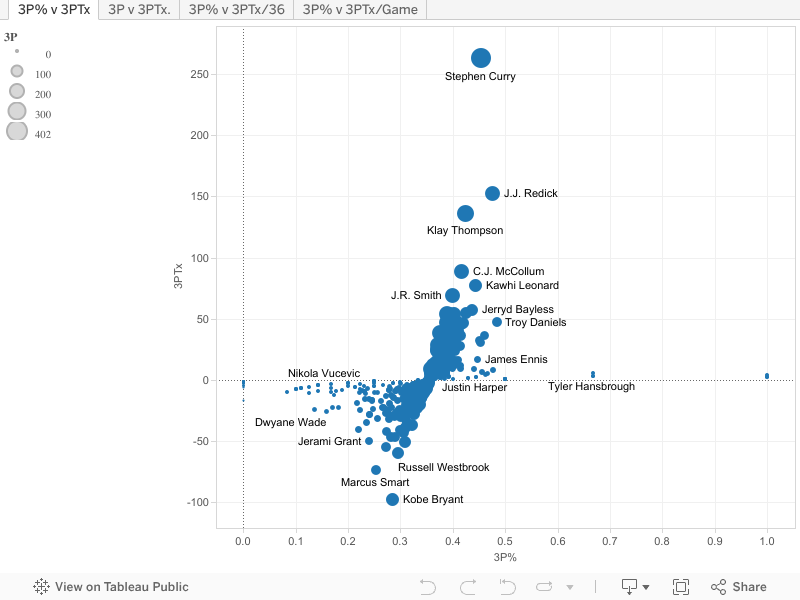

So let’s dive right in and have a look at the results when applied to player data for the 2015-16 season.

If your browser isn’t displaying the embedded graphs above, click here to view the interactive graphs on tableau.com. Scroll over data points for information about that player. To zoom in on a particular area, highlight that area, then hold the mouse over it until a box appears, and click “Keep Only”. Use the tabs up the top to switch between graphs.

First, let’s simply look at 3PTx. To nobody’s surprise, Steph Curry is head and shoulders above the rest of the cohort, adding 263.3 points this season on 3 point shooting alone. More than 100 points behind we have our second tier of shooters, Klay Thompson and JJ Redick, followed by our third tier of CJ McCollum, Kawhi Leonard and JR Smith.

At the other end of the graph, we can see which shooters have been hurting their team with every 3 point attempt this season. At the bottom, with -97.9 points is Kobe Bryant. It’s no surprise, because only Kobe has the respect to keep chucking up low percentage shots and not get benched, and this is a single-season number we may not see again for a long time. Zooming in on the bottom end shows us some of the other players with the worst shooting seasons, including names like Marcus Smart, Russell Westbrook, Corey Brewer, Jerami Grant and Kentavious Caldwell-Pope all garnering scores below -50.

So what can we learn about this graph in general? Well, for those at the very top of the graph, shoot more. For those at the very bottom, shoot less. But for the majority of players clumped into the middle of the graph, it’s a little more complicated. In the middle, it’s best to split our graph along a diagonal line like so:

For those who fall above and to the left of the line, they can attribute their negative score mostly to just being bad shooters. For those who fall below and to the right of the line, their score can be attributed primarily to putting up a volume of bad shots. Additionally, for players who, over the entire season, have a score of -20 or better, it’s worth considering that those attempts might not be that much of a negative influence. For example, players like John Wall or Gordon Hayward, who had season 3PTx scores of -4.0 and -7.2 respectively. Part of the 3 point shot is forcing the defense to respect you on the perimeter. If Wall or Hayward had shot considerably less from 3 this season, they probably would have a harder time getting to the rack as opponents sag off, as well as spreading the floor less for their team mates. So sometimes with players you need to take the good with the bad. However, if Wall had chosen not to take only 4 extra attempts this season, he would have broken even, so players with negative scores should still learn from that statistic when deciding to force a possibly ill-advised 3 point shot.

It’s very interesting to look at where a lot of players lie on this graph, some of the most interesting ones I’ll note here. Marvin Williams is on the same level of shooters as players like Kyle Lowry, Kevin Durant, and Kyle Korver, right at the top of the main pack, proving once again how much of an underrated season he’s having for the Hornets. Players considered by most to be good shooters who had a terrible season: Monta Ellis (-39.0), Nik Stauskas (-27.8), Danny Green (-23.3) and Paul Pierce (-32.5). Also, more proof of how poor LeBron James’ shooting has become this season, costing his team 39.0 points on the 3 ball for only 87 makes on the season. Stop shooting 3s LeBron. Please. Continuing on the stars who shoot 3s too much, Carmelo Anthony (-14.8) hasn’t had a great season. There are also a lot of players considered to be stretch fours or shooting bigs that find themselves with negative scores. Serge Ibaka (-15.8), Kristaps Porzingas (-15.6), Al Horford (-8.4) some of the biggest names, however as discussed before, the floor-stretching they provide may be worth the lost points.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the watershed mark for good or bad 3 point shooting is right around the 35% to 36% mark, which seems to gel with the consensus opinion around the league, which shows that our perception of 3 point shooters is reasonably consistent with game theory.

The 3PTx statistic provides a good look at the overall impact of a player’s 3 point shooting on the season, but a per-shot perspective might give us a better look at which players cause the most damage with every shot, and which players can afford to take more threes to up their efficiency. The next tab on tableau.com displays 3PTx. plotted on total 3 pointers taken. 3PTx. is simply calculated by 3PTx divided by 3 Pointers attempted.

Simply looking at where players fall along a ladder of 3PTx. scores would be interesting enough, but fleshing out the points by looking at total 3s gives us a good idea of how much of a player’s 3PTx. score can be attributed to low sample size, and if so, how many more shots they can afford to take.

Here, we get a better look at some players who have been neglected on the 3 point line. The players we see at the top of the graph with only a handful of attempts can obviously be ignored, because their percentages came off a very small sample size. This metric suffers from a lot of the same flaws as simple 3PT%, but it does benefit from at least giving a reference point of whether a given rate is a good or bad percentage.

For players who find themselves below the 0 3PTx. line, it’s better for them to additionally be found with less 3 pointers made, because the more that come off a bad rate, the more a player is hurting their team. For those above the line, they should want to find themselves with as many 3 pointers made as possible, because each attempt is good for the team. Information about individual players can’t be explored as much as with the previous graph.

The third graph plots 3PTx/36, a measure of how many points a player adds through 3 pointers per 36 minutes of court time. Steph Curry finds himself highest amongst high volume players, to no surprise, but we also find a few players around his range whose value on the court may have been overlooked when it comes to the 3 pointer. Steve Novak and Troy Daniels stand out the most, but obviously these players have bigger flaws in their game which force coaches to sit them, despite their good 3 point shooting. This measure is best for judging players in the middle of the pack and comparing similar players, just like other /36 statistics.

The final graph plots 3PTx/Game, another metric which provides a good equaliser, however this stat is more effective for multi-season comparison, or contextualising a number. This graph will be much more interesting when comparing historical players, whereas for single-season data it looks almost exactly the same as the first graph which simply plots 3PTx.

It should be seen from this rudimentary exploration of the results how effective 3PTx is as a measure of 3 point shooting. This statistic would be a good advanced stat to use in analysis of a player’s shooting, and provides a single number on the level of box-plus-minus or Win Shares which immediately allows one to make conclusions about whether a player’s shooting is a negative or a positive. In my next article, I will be applying this data to historical 3 point shooters and subsequently judging the best and worst players of all time when it comes to long-range shooting. Further down the road, I am looking to try and implement a similar strategy to a player’s entire scoring output, to discover who the best all around scorers of all time are. But until then, enjoy the use of this metric for analysing 3 point shooters. Contact me if you’ve got any suggestions for how this metric could be improved, or your general thoughts.

- statistics provided by Basketball Reference

- Graphs provided by Tableau.com

- Read about how this statistic applies to all-time 3 point shooters here

- twitter: @jackneubecker

- email: pointforwardpod@gmail.com

- An Article by Jack Neubecker

You must be logged in to post a comment.