What follows is the academic residue of a spirited discussion between a fellow PhD student and myself, concerning the use of measure theory in probability. The central question is “Why bother?” Here is my attempt at an answer to this question, through a small demonstration of measure theory’s ability to generalise. This is not an attempt to teach any measure theory, but I will point to a few resources at the end that I found helpful for reacquainting myself during our discussion if you would like to do the same.

The traditional result

First, we must establish in traditional terms the result we will later emulate measure-theoretically. I will only talk about non-negative random variables; the result generalises by splitting into positive and negative parts, but the notation is drastically simplified.

Theorem 1: If is a non-negative random variable with density

and probability function

, then

.

Proof:

There are two conceptually important points here. The less theoretically troublesome one is the switching of integrals, which Fubini lets us do, but I’ve always found a little cheeky. More foundationally important is that we assume the existence of a density here, but it is absent from the result of the theorem. It is an achievable exercise to prove the equivalent result for discrete distributions, and I concede that most continuous distributions I have encountered in the wild have a density, but this does have practical importance. The usefulness of the theorem is in being able to compute an expectation when we don’t have or don’t want to find a density, so it’s essentially useless if having a density is a pre-condition to its application. Can we get around this somehow?

In steps measure theory

I will spare the majority of the details of satisfactorily defining a random variable measure-theoretically, but some objects need to be defined.

The premise of measure-theoretic probability is that we start with a measure space . In probability terms, this gives us a sample space

, a set of events

and a probability measure

, as long as

. We will brush over what

is really saying, but suffice to say it imposes Kolmogorov’s unit measure axiom. The other axioms of probability are packaged up in what a measure space is. This gives us a notion of what probability means on

. We can then define a real-valued random variable as a measurable function from

to the reals, that is, a function

such that the pre-image

of any open interval

is an element of

.

For our purposes, we can define any real-valued random variable as follows, by first defining the distribution. Take

to be our measure space, where

is the set of Lebesgue-measurable subsets of

, and

is the Lebesgue measure. Then the uniform distribution

can be defined as the identity map

. You can check for yourself that any property you like about the uniform distribution carries over perfectly. In particular, we can check that

.

Now, anyone familiar with the inverse-transform will know that defining any other real-valued random variable is a piece of cake. Every real-valued random variable has a distribution function

, so we define

.

might not be easy to compute, but it definitely exists.

We are still missing one key element, expected value. We define it as . I will leave undefined what it means to actually compute an integral this way, but it can be done. Importantly, it is still achieving the same goal of finding area under a curve. We are now ready to prove:

Theorem 2: If is a non-negative random variable with probability function

, then

.

Proof:

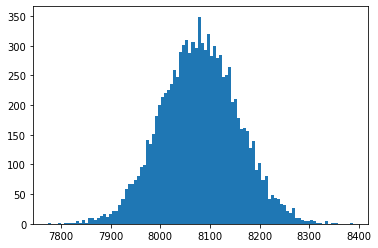

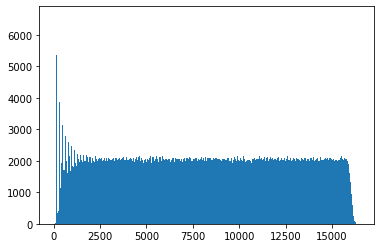

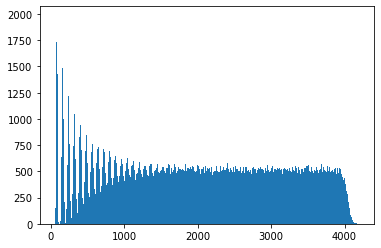

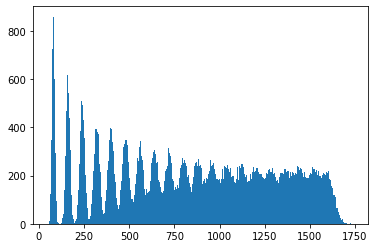

If you’ll allow me a couple of pictures, I argue that it is true by definition. We see that the area integrated by and the area integrated by

are in fact the same areas.

Q.E.D.

Some healthy skepticism

Now, we should be skeptical of any proof which follows so readily from the definitions. The traditional discrete distribution is marvelously intuitive. Further, we can squint at the traditional continuous expected value definition and notice the pattern. By comparison, the measure-theoretic definition is quite opaque. So far it seems like we just made up a definition so that this proof was easy. What’s the value in that? Here’s how I see it.

I liken it to the intermediate value theorem (IVT). The point of proving the IVT is not to dispel any doubt that if an arrow pierces my heart it must also have pierced my ribcage. The point of the IVT is in showing that the definition of mathematical continuity we have written down captures the same notion of physical and temporal continuity we sense in the real world.

What we have really learned from theorem 2 then, is that we can define expected value in terms of the probability function directly. We essentially drop the density assumption by fiat. The value is in discovering this more powerful definition which unites previously disparate discrete and continuous cases, as well as distributions which are a mix of both.

A concrete mixed distribution example

My favourite mixed distribution is the zero-inflated exponential, with probability function when

, and

otherwise.

Traditionally, to evaluate an expected value we would have to be rather careful or apply some clever insight. Now with measure theory, we can ham-fistedly shove straight in to

and call it a day.

We can also start sparring with more exotic random variables on non-numeric spaces with confidence. I’m currently working through Diaconis’ Group Representations in Probability and Statistics, so hopefully I can speak on these “applications” in more detail in the future. But for now, I’ll leave it as an enticing mountaintop rather than trying to spoil the ending.

Intuition

It is no secret that I don’t like the IVT, or theorem-motivated definitions more broadly, so I am uncomfortable leaning on it in an argument. What I will provide here is my own post-hoc intuition for the measure-theoretic expected value. Rather fortuitously it leans on the IVT, so I’ll point out pedantically that I’m actually using it as the Intermediate Value Property (IVP) in and of itself. Observe below that the area on the left is the area defining a measure-theoretic expected value as we have seen above.

Note that this area is the same as the area of the rectangular region. As it has unit width, its height is also its area. This height is not coincidentally the mean value of guaranteed by the IVP, so we see that the measure-theoretic definition gives us a measure of central tendency. That this is the same measure of central tendency as the traditional definition can be shown in many ways, but we have seen it today as a porism of theorem 2.

What have we learned?

In short, that generalisation is cool, and measure theory is not as scary as I thought after failing it in third-year. It gives us steady footing to go and explore exotic spaces, and it provides some nice perspectives on old favourites. Is it of practical use to the working statistician? Debateable. Our main theorem can certainly be used without actually doing any measure. Perhaps it provides nice perspectives on transformations if one does need to compute certain integrals which aren’t recognisable. What do you think? Have I convinced you measure-theoretic probability isn’t useless? Do you know any interesting applications I didn’t mention? As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Resources

I am always hesitant to endorse texts based solely on how helpful they were to me. We should remember that one always understands something better the second time. That being said, the following two probability-oriented texts were useful to me. Matthew N. Bernstein has a trio of nice blog posts entitled Demystifying measure-theoretic probability theory, which are a nice, slow introduction to some of the basics. I also found Sebastien Roch’s Lecture Notes on Measure-theoretic Probability Theory useful as a much denser, more comprehensive reference. As for strictly measure-theoretic principles, I found plenty enough information by simply clicking the first Wikipedia article to pop up when I searched the relevant terms.

You must be logged in to post a comment.